05 — 08.05.2017

Marlene Monteiro Freitas Lisbon

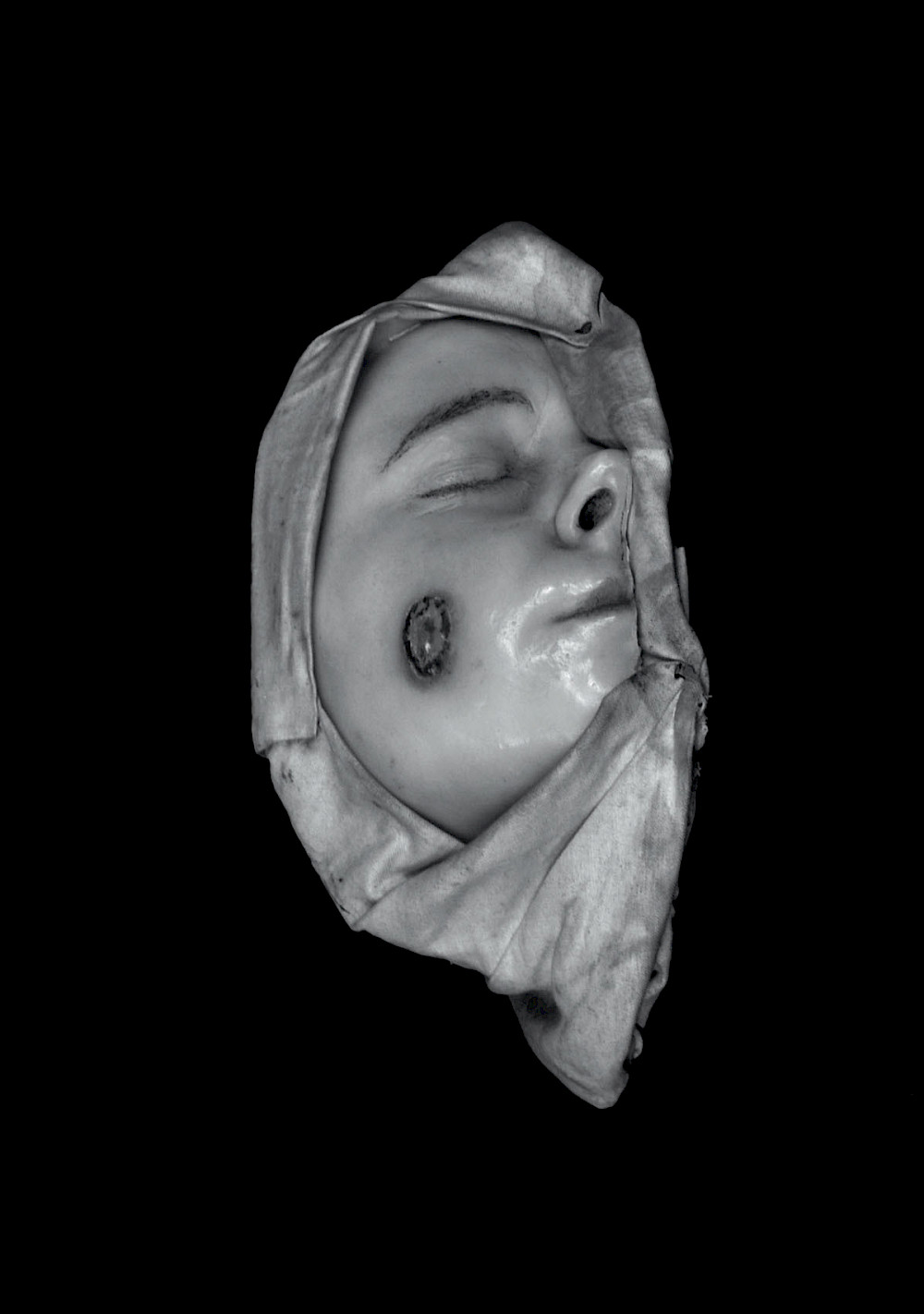

Bacantes – Prelúdio para uma Purga

dance — premiere

⧖ 2h30 | € 18 / € 14

One of the greatest discoveries on the international choreographic scene, Marlene Monteiro Freitas fascinates audiences with her language of abundant vitality, her strong imagery and her wealth of references. In her works characterised by excess and expressivity, heterogeneous, disturbing and funny elements are combined with limitless creativity, like parts of a spectacular machine producing sensations. Her latest work, coproduced by the Kunstenfestivaldesarts, is also her most ambitious. Based on Euripides’ The Bacchantes, twelve dancers and musicians tackle the Greek tragedy – for Nietzsche, summoned here, the very illustration of the metaphysical function of art. Marlene Monteiro Freitas’ Bacantes are a war between the Apollonian and Dionysian, reason and intuition, form and dissolution of the form, individuation and self-denial. They also question art, life and art as the affirmation of life.

See also

Beyond the Codes

The meaning of fictions

Interview with Marlene Monteiro Freitas

You were born in Cape Verde where you started dancing at a very young age. What training did you have back then? Do you remember anything from that time that made an impression on you?

I started dancing with friends when I was young. At the age of fourteen, we decided to stage some shows. We chose a name for our group, Compass, and performed shows in cinemas or outdoors, exploring all kinds of music and dance. Our curiosity was very eclectic; from the film Jesus Christ Superstar to hip-hop clips, by way of images of samba, salsa and Cape Verdean dances… We looked at videos and magazines and we used to design and make our costumes. We learned about styles of dance that we didn’t really know and then came up with our own ideas. And then there was a very significant moment: a Portuguese choreographer, Clara Andermatt, came to Cape Verde for a residence. She gave a workshop, where I was able to take some lessons, and she presented a piece that she was in the middle of creating. I remember being completely moved by it, I felt like a sack of bones that had been completely shaken. That was when I must have told myself that I, perhaps, could do the same thing.

At 18, you left Cape Verde to study in Lisbon.

As a part of a scholarship programme I went to physical and sports education university that had a dance department, but I realised straight away that the dance lessons at this school weren’t what I was looking for. I finished the first year so that I could keep the scholarship and then enrolled at the Escola Superior de Dança in Lisbon.

Back then in Lisbon, there was an established choreographic scene already, with artists like Vera Mantero, João Fiadeiro, Clara Andermatt, Paulo Ribeiro and Francisco Camacho… Did you have any contact with those dancers and choreographers?

Not really, no. I only started to come in contact with them, particularly Clara Andermatt and Francisco Camacho, when they were invited to the school. I remember seeing a piece by Francisco Camacho, GUST, which made a big impression on me. After which I worked for him, as a stand-in for one of his performers in a show. But I did have contact with a Cape Verdean choreographer that I already knew, António Tavares.

After the dance school in Lisbon, you continued your training at P.A.R.T.S. between 2002 and 2004. What took you to P.A.R.T.S. and now, some ten years later, what do you remember of it?

What took me to P.A.R.T.S.? A combination of luck and desire to live inanother European city. I wanted to have a better understanding of whathigh-quality training in contemporary dance could be like, but it wasclear for me that P.A.R.T.S. wasn’t a school in the classic sense of theword. In any case, I never thought that you had to expect everything froma school. School is a place of transition, a passage that you should benefitfrom as much as possible. It is a place to be confronted by differentaesthetics. Going to P.A.R.T.S. gave me very important working tools andideas for compositions… It was a site to collect information so that somethingelse could emerge. What I didn’t know was that it was up to me toundertake this work.

After P.A.R.T.S., you worked for choreographers from quite different worlds: in France with Loïc Touzé, Boris Charmatz and Emmanuelle Huynh, and in Portugal with Tânia Carvalho…

After I left P.A.R.T.S., I did a few auditions in Portugal, but I wasn’t offered anything. In the end, I replaced a dancer in the Contemporary Dance Company of Angola for a tour in India and then I replaced someone else in a show by Tânia Carvalho without really knowing what I was going to do afterwards. Then I took a choreography course at the Gulbenkian Foundation in which Loïc Touzé was involved. I was very shy, we hardly talked, but then Loïc Touzé invited me to do a project with him. In the beginning, I understood very little and the way of thinking about things and tackling them was different from what I’d experienced up until then. Without doubt, this was the first time I realised that there was some sort of common within this idea of contemporary dance in Europe, but that it could be expressed very differently depending on the country and depending on the school… All the choreographers I’ve worked with have inspired me hugely. Even when with someone or in certain situations where I could potentially feel very distant it seems that when ‘sympathy’ and ‘antipathy’ are present, images and ideas do emerge.

In 2011, you created (M)imosa, which is the result of a choreographic collaboration between you, Trajal Harrell, Cecilia Bengolea and François Chaignaud based on the New York culture of voguing. It’s quite an astonishing piece where the things that make you stand out from one another coexist very powerfully. What was the creative process behind it like?

It was very clear at the start of the project that the four of us would be co-authors. We went down a common path towards the idea for the project, but each of us had our vision and our own way of working. Each of us had propositions and tried to take the others in that direction. Then we understood that the piece should really be like a four-headed animal with none of us ‘making room’ for the others (I really don’t like this idea of trying to make room…). Instead, we wanted to allow for a reciprocal confidence to emerge. So it was about being able to perform with a certain freedom, each in our way, and that led us to intensify each of the four contrasting propositions.

Why don’t like the idea of ‘making room’?

I’ve got a problem with the performance of generosity. This idea of ‘making room for the other person’ has a moral side to it, a rhythm that worries me a bit. In my work, I prefer the idea of fiction. It’s rhythmically more uncertain, freer. Like in dreams where despite ourselves, the images, gestures, attitudes and their organisation escape us.

When did this idea of fiction really start to make itself felt?

I think it came from a piece called A Seriedade do Animal that I made in 2009-2010. It is based on a text by Brecht called Baal. Even though we didn’t say the words, we followed the framework of the piece from start to end, and the rhythm of the show came from a certain idea of its oral character. But it was with Guintche (a solo created in 2010) that I actually had to start formulating this notion of fiction. I was asked a lot of questions when Guintche was performed, then close friends of mine came up and told me that I was very different, that they didn’t recognise me… But in fact, without having given it a name at that point, this idea of constructing fictions was already present. Guintche combines a work on movement, with a very sustained rhythmical foundation, and the construction of a character (perhaps this ‘fiction’ you’re taking about).

What took priority when you were developing this solo: the movement or the character?

‘I prefer to talk about ‘figures’. A character summons up a certain context, whereas a figure can imagine its context. I like situations, not stories or narration. A painter like Francis Bacon works on the figure and situation, but not the narration. He says: “The moment the story enters, the boredom comes upon you.” It’s the same for me. I’ve never been preoccupied by this question of abstraction and narration, which is very present in dance. Perhaps that’s why I look beyond dance for inspiration. It opens up other ideas, other images than those that you share in dance and call ‘abstraction’ or ‘expressionism’. You asked me how I start a work? With lots of things all at the same time. Images that are without me knowing exactly why, but nevertheless, I take them into account. It’s always a bit chaotic and a bit methodical; I have an idea of the direction to take – that the music is going to intervene in a particular way… And then in the studio, a certain number of transformations occur.

Don’t you feel a need to position yourself among contemporary choreographers, to be influenced by a particular trend?

No. I love seeing shows, I love what lots of artists do, it would worry me if we all had to resemble one another and act in the same way or in the creation to one another. There’s a diversity of routes you can take in the creation of dance, but there’s also theatre, cinema, music, the arts, the internet, YouTube, thoughts… Limiting yourself to dance or confining it to restrictive concepts such as post-colonialism, feminism etc. is not my way of working, thinking or living. Contemporary dance escapes frameworks, sometimes people seek to ‘capture’ it, as if you have to calm down the tremors a show can induce…

You have a taste for hybrids and metamorphoses. Where does this come from?

I really don’t know. In fact the hybrid is not an end in itself, but more so a way of achieving a certain intensification of the form. The organisation of very diverse, even contradictory things produces emotion. Often in the pieces there are images in the process of becoming something else. This has to do with the fiction, with the transformation. Very simple ideas and images often constitute the starting point, but we work on it a lot to draw out something like power. In the end, something comes out of it that is still recognisable, in which you could identify a starting point, but perhaps notice that it has profoundly changed. That’s the key driver behind the work. You could say that metamorphosis has a transgressive side, but it’s not the transgression as such that interest me, it’s more so a way of achieving a certain overflow.

Jean-Marc Adolphe

An extended version of this interview was published in P.A.R.T.S: 20 years – 50 portraits (2016)

Choreography

Marlene Monteiro Freitas

With

Andreas Merk, Betty Tchomanga, Cookie, Cláudio Silva, Flora Détraz, Gonçalo Marques, Guillaume Gardey de Soos, Johannes Krieger, Lander Patrick, Marlene Monteiro Freitas, Miguel Filipe, Tomás Moital, Yaw Tembe

Light & space

Yannick Fouassier

Sound

Tiago Cerqueira

Stools

João Francisco Figueira, Miguel Figueira

Thanks to

Cristina Neves, Alain Micas,Bruno Coelho, Christophe Jullian, Louis Le Risbé, Manu Protopopoff, ACCA – Companhia Clara Andermatt (Lisbon), ESMAE (Lisbon), ESTC (Lisbon)

Presentation

Kunstenfestivaldesarts, Halles de Schaerbeek

Production

P.OR.K (Lisbon)

Distribution

Key Performance (Stockholm)

Co-production

Kunstenfestivaldesarts, TNDMII (Lisbon), steirischer herbst festival (Graz), Alkantara (Lisbon), NorrlandsOperan (Umeå), Festival Montpellier Danse 2017, Bonlieu – Scène nationale d’Annecy & La Bâtie- Festival de Genève in the framework of FEDER – programme Interreg France-Suisse 2014-2020, Teatro Municipal do Porto, Le Cuvier- Centre de Développement Chorégraphique (Nouvelle-Aquitaine), HAU Hebbel am Ufer (Berlin), International Summer Festival Kampnagel (Hamburg), Athens and Epidaurus Festival, Münchner Kammerspiele, Kurtheater Baden, SPRING Performing Arts Festival (Utrecht), Zürcher Theater Spektakel (Zurich), Nouveau Théâtre de Montreuil – centre dramatique national, Les Spectacles Vivants/Centre Pompidou (Paris)

Residency support

O Espaço do Tempo (Montemor-o-Novo), Montpellier Danse à l´Agora, cité internationale de la danse, ICI-centre chorégraphique national Montpellier – Occitanie/Pyrénées – Méditerranée/ Direction Christian Rizzo – in the framework of the residency programme Par/ICI

Project co-produced by

NXTSTP, with the support of the Culture Programme of the European Union